George Thompson in his book “Faded Footprints” relates the following story:

“There are old Spanish mines all along Currant Creek Canyon; too many have been found there to doubt that. One of those found mines has had a long and sometimes bloody history. Fifteen miles up Currant Creek Canyon from Highway 40, there is a dirt road which climbs steeply to the northeast. If you stop about two miles along that road and look to the east, a high outcropping of red sandstone ledges can be seen through the aspens. A short hike across a small creek and past some swampy ground leads to two caved mine tunnels driven into the mountain just below those red ledges. The waste dump at their portals is becoming difficult to find now, being heavily overgrown with white-barked aspens and second growth pines. If you take your time and keep a close watch, you might spot a few rotted logs where a cabin once stood. Part of that cabin was still standing and one of those tunnel portals was still open when I first saw them more than forty years ago. At that time there was a vertical shaft just north of those tunnels, close under the ledges and northeast of the cabin site. High on those ledges there is a large outof-place square boulder which some say covers yet another shaft. Although those red ledge tunnels and shaft have been on Forest Service land for one-hundred years or more, just recently they were claimed by the Ute Indian tribe. The Forest Service granted the Utes a special mineral exemption to that area, placing those tunnels off-limits to non-Utes. I wonder why?

Stockmen from Heber Valley first discovered those old mines in 1908, as was reported in the Wasatch Wave at that time. That article described Spanish tools and other artifacts which were found in those tunnels” (pg, 62)

The red ledges at Currant Creek were an active mining area for the Spanish.

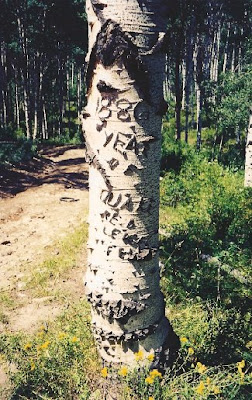

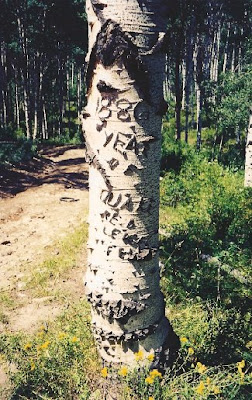

This tree reads – “1880 year of quake – red ledges fell”. Due to this quake, most of the mines in this area are collapsed and inaccessible.

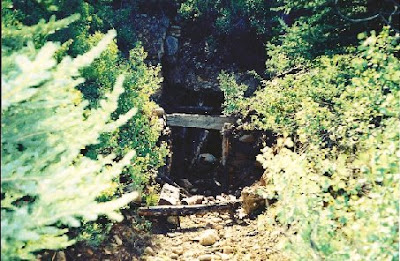

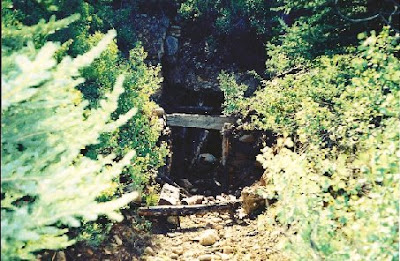

Here is the opening of the original Spanish mine after it was reworked by a mining company in the 1940’s and 50’s.

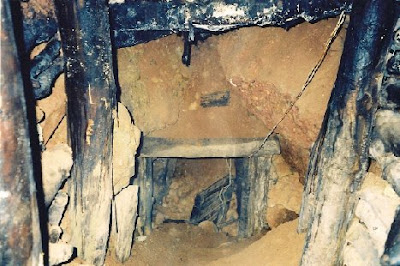

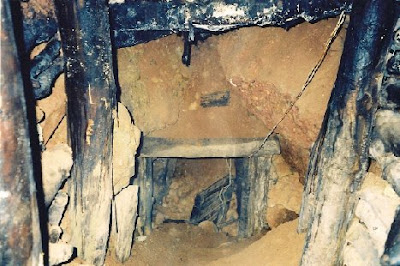

Just inside the tunnel.

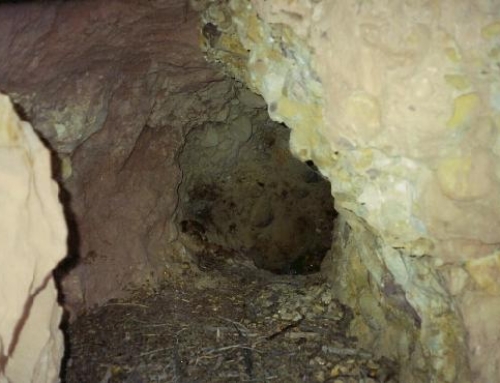

This is where the mine caved in. It does continue a little ways past here since someone has been digging it out.

This is an old tailing pile. As you can tell by the two pine trees growing out of the top of it.Gale Rhoades in his book “Lost Gold of the Uintah” also tells the following story of the red ledges mines.

The red ledges at Currant Creek were an active mining area for the Spanish.

This tree reads – “1880 year of quake – red ledges fell”. Due to this quake, most of the mines in this area are collapsed and inaccessible.

Here is the opening of the original Spanish mine after it was reworked by a mining company in the 1940’s and 50’s.

Just inside the tunnel.

This is where the mine caved in. It does continue a little ways past here since someone has been digging it out.

This is an old tailing pile. As you can tell by the two pine trees growing out of the top of it.Gale Rhoades in his book “Lost Gold of the Uintah” also tells the following story of the red ledges mines.

“We drove up the old road to a point only 200 or 300 yards from the Red Ledge, at which point Leland left the road and drove down through the pines and quakenasps, where there was no road at all, to our final destination – a small basin at the base of the ledge. It was either late November or early December (1968) and although the ground was moist and partly frozen, there was very little snow, so we had no trouble at all getting in or out of the area.

What we discovered in that small basin was quite surprising. There was the remains of a very old cabin, just a few logs of its walls were still standing, and three distinct but ancient mine dumps – long dumps which had been pulled from the mountain. Two of these mines had long ago collapsed and very dangerous to enter. These had all been explained to me, in detail, be Mr. Wells during my many interviews with him over the years, but they were not the small shaft where Noyes and Sharp had retrieved the two bags of gold before being caught redhanded by the Indians.

Acting upon instructions given me by Mr. Wells, we set about in search of the ‘tree-ladder’ and the ‘shaft’ near the base of the Red Ledge. Dropping away from the ledge, I noticed a large quakenasp with some sort of markings carved on it, and upon closer examination found the markings to be that of a man with a hat and the date of 1850. While standing there looking at the tree symbols, I happened to glance past the tree and could see about 50 feet below a long, large log nearly covered by leaves and debris which had been shaven flat on the upper side and embedded almost completely into what appeared to be some sort of a dump – it had been used as a smooth platform for the wheels of a wheelbarrow or something of that sort. At the back end of the platform, at the base of the hill on which I had been standing, was a small depression, covered be a large piece of tin and earth, which had sluffed in at one side exposing what appeared to be a shaft. I hollered to the others and they joined me in inspecting my find. It was an old shaft, which intersected one of the old collapsed tunnels, but it still was not the one described to me by Mr. Wells.

Even so, several interesting objects were found laying around near the old ‘covered’ shaft. Right near the shaft were three or four old buckets which were made of hand-wrought iron and wooden slats, and to the right laying among the trees was a large cable winch of 1890 vintage which must have weighed 200 to 300 pounds, and near that – scattered about in pieces – were its frame posts and gears. Below these objects and not far from the old cabin, carved in large letters upon an old quakenasp tree, were the initials “E.R.” I wonder if they were not those of Enock Rhoades. Another set of initials not far from the Red Ledge were those of “CRB,” the same of Caleb Baldwin Rhoades, but scrambled.

At the sight of these mines there were countless old pine trees which had been cut down, probably for use as mining props, but for some unknown reason were left in tact where they had fallen, untouched as it were, as if the miners had been forced to flee the area on very short notice.

Just over a small rise and to the west of these mines was found another mine tunnel, also collapsed at a point about 15 feet back in. There was a dump in front of the mine upon which there was found an old ore car track or rail made of wood, a shaved pole of a tree. Nearby, the remains of an old ore car wheel, also made of wood.

Needless to say, we were quite excited over this discovery, especially in light of the fact that I had spent three long years sifting through hundreds of notes from interviews with Noyes, Wells and Petitti trying to narrow the location of the mines down to an exact location. The closest we’d been to the mines during previous search attempts was about five miles away, to the north.

The one thing which surprised us most, perhaps, was the fact that these mines were no longer upon the Indian reservation. They were now located upon National Forest lands which were normally open for the purpose of filing mining claims. With this in mind, we set about immediately to determine what should or should not be claimed and then Jay and Leland drove to the Duchesne County Courthouse to check the land status records to make certain the land was clear of any previous claims before erecting our claim monuments.

Unfortunately, upon checking the land status records, it was found that, although this land was forest land and not reservation land, the mineral rights belonged to the Indians. The land was removed from the reservation during the late 1930’s, but as a trade off with the Indians for other land the mineral rights to this land (10 square miles) was given back to the Indians by Public Law 717 – 84th Congress, Chapter 603 – 2nd Session, H.R. 7663, in 1956. Our dreams of locating the Rhoades Mines and placing them back in production vanished.”

Leave A Comment