The following story comes from an article in the Daily Herald but the pictures were obtained from the owner when the horns were in the old Current Creek lodge. This could be a just a rare incident where the rams horn became stuck, or an Indian could have hung him there long ago, but the owner has possibly found a connection to a forgotten treasure that the horns may be marking.

“Ron Sweat owns the 8-foot juniper trunk holding the horns, and though reluctance plays out on his face, he knows that at age 64, and with his wife ailing, this astonishing spectacle of natural history now represents his best hope of a retirement nest egg.

Having flatly rebuffed a $100,000 offer, Sweat is seeking no-nonsense buyers with hefty wallets. Though he is not an expert, Sweat has counted the tree’s rings and believes they prove the tree dates to 1486, “six years before Columbus.”

If the ram’s horns are not piquant enough, the trunk also houses the shafts of what Sweat believes to be two American Indian arrows. Slivers of wood from both have been tested by the University of Utah; one came back as greasewood, the other pine, he said. A mysterious square peg embedded in the tree has tested as ash.

Sweat’s tale begins with his father in 1944. It was in the winter of that year that the elder Sweat followed the old Spanish Trail on a two-day camping trip into the wilds of Current Creek Mountain to run a trap line. A native of the land who knew the landscape better than most people know the interior of their homes, the elder Sweat “had a tremendous knowledge of the area,” Ron Sweat said.

During that fateful trip, his father stumbled upon the horns and skull of a desert ram, fully encased in what had been a crotch of the tree. He also found, somewhere in the area, a tallow lantern and what he described as the head of a Conquistador axe, also both enclosed within the wood of a second juniper.

Sweat said his father told him that part of the wooden handle of the axe remained, and that his father picked up the loose wood remnant, examined it, and put it back into the embedded axe head. He has searched extensively for the lantern and axe, to no avail.

The elder Sweat could not keep himself from telling friends and neighbors about his discovery, and in 1950, on a trip to cut cedar posts to make a corral with, he returned to the tree, taking his two brothers with him to show them his discovery.

“The manager of the natural history museum in Vernal told him to go cut the tree without damaging it and he would stop by and look at it, and if it was what Dad said it was, he would give him $75 for it,” Sweat recalled his father telling him. “That was two months wages back then. That was a lot of money.”

When his father declined, his two brothers snuck back to the tree in 1951, cut it at about two and a half feet off the ground, and secretly sold the trunk and embedded horns to the owner of a local lodge. The brothers were paid $50.

For a full year the lodge owner kept secret his purchase, but eventually he could not resist putting his treasure on display in the lodge. When he found out what his brothers had done, “Dad was a little bit pissed, because that was his tree,” Sweat said.

From 1951 on, the tree was displayed in the lodge. In 1961 the elder Sweat died having left no written record of his discovery, though he told his story to many.

In 1983, perhaps partly to get back what his father had lost, Sweat bought the lodge.

In 1985, the story of the tree took an enigmatic turn when one day a Summit County surveyor happened into the lodge for lunch. When he saw the tree, he was gobsmacked.

For the next 20 years, the surveyor would become an intricate part of the story of the tree. The surveyor told Sweat that while doing a research project in the library of a university in Texas, he had happened upon the journal of a Spanish Conquistador. The journal told a very specific story about a group of Spaniards trekking through the West on a journey funded by a Jewish aristocrat in Spain who had “sent his son along to protect his interest,” Sweat recalled the man telling him.

The journal’s tale was convoluted and lengthy, but in the end the aristocrat’s son cached a treasure of gold by marking the spot with a desert ram’s horn in the crotch of a tree, along with a ritual ceremony marking the tree. The son and his crew of 11 men never arrived back at the rendezvous point near present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico. Two search parties over the next year failed to find a trace of them, or the cache.

Sweat says he has searched extensively for the gold and believes it has long since been taken. The surveyor has flown back to Texas and searched for the book he read in college, but neither he nor library staff have been able to find the journal.

Sweat’s father died when Sweat was about 17 years old, without ever having shown his son exactly where he had found the tree his brothers had cut down, though he had told the younger Sweat how to find the general area. Over the years, many people who came into the lodge claimed to have been told by the elder Sweat where the tree stump remained.

“I got reports that it was from everywhere,” Sweat says with a smile.

Then one day, a mysterious woman came to the lodge and told him not only details of how his father found the tree that Sweat had never known before, but also detailed directions to the stump. As the woman began to leave, Sweat begged her to go with him to the stump, but the woman said she had given him more than enough information and promised he would find the stump without trouble.

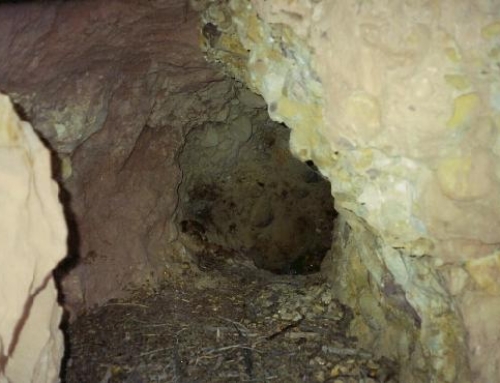

Which he did.

Not only does the stump perfectly fit the outline of the tree trunk, but it has the other half of what Sweat believes to be a peculiar Conquistador marking on the trunk he owns. It is unquestionably the stump where his father found the tree in 1944, Sweat said.

How did the mysterious woman know the exact location of the stump, and new details of the story of its discovery?

Faced with this question is the only time during his Daily Herald interview that Sweat demures.

“She was psychic, I guess,” he says, his face a perfectly expressionless poker-player’s visage. Then his eyes shift to the ground, perhaps belying that there is more to this part of the story than he wants to tell now.

In 2001, Sweat sold the lodge, keeping the tree trunk and horns for himself. The lodge has since been torn down. After a half-century in the public eye, the tree trunk has been put away in a safe place. Sweat asked the Daily Herald not to reveal both where he lives or where the tree trunk is stored, for security reasons.

There is one more reason why the tree might be very valuable, he said. It appears to qualify, through a complex scoring process, as one of the top three largest pairs of desert rams horns to ever be measured. Collectors pay large sums for world-record desert ram horns that are modern; the unique nature of Sweat’s pair of horns would presumably only drive up demand and value, perhaps meteorically so, he said.

For those who might, upon reading this story, decide to hunt on their own for the stump of his tree, or the lantern and axe, Sweat wishes them luck.

“There are a million or two junipers on Current Creek,” he says in his slow voice.

A taxidermist has recently cleaned and whitened the skull, in the process removing the historic patina. Sweat said neither the tree nor horns have ever been seen by experts because “I just haven’t gotten around to having it examined.” He pauses. “I’m kind of scared of too many people knowing that I have it because it is one of a kind.”

Sweat also has one of the spinal bones of the ram that was found with the skull; the bone is a perfect fit at the base of the ram’s skull.

Sweat would like to have the entire 400-pound trunk X-rayed to reveal the embedded horn and to see if the arrow shafts have arrow heads on them.

He is prepared to sell the tree trunk and horns “at a price,” he said. “I would like to sell it to a museum so people can look at it, but I am not going to give it away.”

Sweat also said he will take the buyer to the tree’s stump.

Interested parties are asked to contact Sweat’s agent, Cary Seegmiller, at 801-687-2000.”

Leave A Comment